I gave this post a tag I haven’t used before: Politics. Although this blog is almost five years old and some of the posts have touched on political matters, I never used Politics as a tag before now. That was by design. When I created this site, I envisioned it as a place to reflect on the stories we tell ourselves to make sense of life in the modern world. Rather than writing about particular controversies in the political arena, I wanted to take a broader view of the underlying cultural issues.

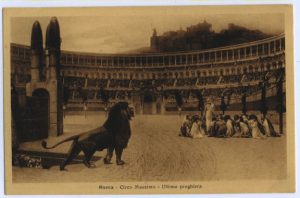

I didn’t give much thought to the arena itself—a word that now strikes me as quite apropos in light of recent events that brought to mind the Circus Maximus, complete with gladiators, lions, condemned Christians, and a gleeful crowd of bloodthirsty spectators. Although the dysfunctional American two-party system obviously has been far from ideal for many years, I assumed it was a short-term problem that would improve as people became more comfortable in a changing world. It’s now clear just how far off the mark that complacent assumption turned out to be.

(Creative Commons image via flickr)

How did we find ourselves in this dystopian alternate reality where discussing candidates’ qualifications and voting in national elections, which used to be seen as a shared moral obligation to exercise civic responsibilities prudently for the good of the community, now amount to fighting on a bloody battlefield in a cultural civil war where nothing matters but winning at all costs?

A large part of it, I would say, is in the words we use—war, battlefield, fighting. Reading them just now, you probably didn’t think twice about it because we’ve all gotten so used to seeing political differences of opinion framed in such terms. Journalists do it all the time. Advocacy organizations routinely send out appeals for help with the fight against this, the war on that, and the battle for whatever. War metaphors have reached saturation level in our society. Most of the time we don’t even consciously notice them anymore; but in the murky depths below the surface of our awareness, they’re wreaking havoc on our collective psyche.

It’s not that we literally see as enemies the family down the street who put up a yard sign supporting the other party’s candidate. Most of us are civil enough in real life that we’re still going to smile and wave when we pass by their house and see them in the yard, even if we later grumble to ourselves that they should have known better than to fall for the other party’s propaganda. But when we turn on the talk shows, get into conversations about politics online, or go to rallies where our candidate whips up the crowd into a frenzy, the usual rules of civil society fall by the wayside. The insults fly fast and furious, until it starts to feel like that’s the normal way of things.

When we look at the political divide as a war, rather than as a mutual lack of understanding and a failure to communicate, we close our minds to any prospect of finding solutions through respectful dialogue and cooperation. Destroying the other party seems like the only way to get anything done. Primary voters don’t look for moderate candidates who would try to work productively with the other party because that seems downright impossible. After a while, extremists sound like they’re only being realistic.

To change things for the better, we’re going to have to take responsibility as individuals to make decisions based on our shared cultural values, including civility and respect. A good place to start would be to pay more attention to our word choices and replace those war metaphors with calmer and more constructive language. Social issues and political disagreements don’t always have to be fights and battlefields. We need to find a better way, for everyone’s sake, because ultimately we are all on the same side.