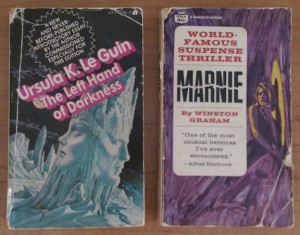

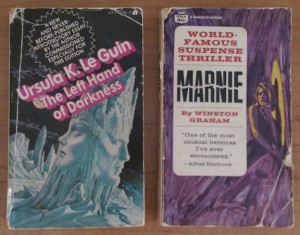

Among my blog posts this past winter, I wrote about stories remembered from childhood and how they have a subconscious effect on perspective in adult life. I mentioned two novels on my bookshelf that had influenced my worldview as a teenager. One of them was The Left Hand of Darkness, which encouraged me to trust my intuition and to believe I could change the world, while also leaving me fearful that taking decisive action might lead to being attacked by enemies. The other was Marnie, which I decided to leave for more discussion later.

Marnie is a young woman in the early 1960s who lives in England (unlike Hitchcock’s movie based on the book, which is set in the United States instead). She grew up poor, raised by her mother after her dad was killed in the war. Leaving school at a young age, she became a thief. She takes jobs under false names, enjoying the drama of inventing new lives for herself, and steals the payroll (in those days, wages usually were paid in cash).

Although she uses some of the stolen money to support her mother, who doesn’t know what she has been doing, Marnie spends most of it on herself. After every theft, she lives comfortably for several weeks at an inn under the pretense of being a wealthy lady, with nothing to do but ride a horse that she keeps boarded at a riding stable nearby.

Eventually she lets too much slip about her personal life when talking with Mark, a part-owner of a printing company where she works. When she absconds with the payroll, he quickly tracks her down. But instead of turning her over to the police, Mark tells her that he has fallen in love with her, and he proposes marriage.

Rather than counting herself lucky, Marnie feels trapped and resentful. She hates the whole idea of being married, but she goes through with it anyway because she doesn’t know what else to do. She daydreams about running away to France, and she gets even angrier when Mark insists that she visit a psychiatrist regularly and when he wants to repay the money that she stole from past employers.

After her mother dies suddenly, leaving some ugly secrets exposed, Marnie decides not to run away after all. She feels that there is nothing about her old life that she wants. Even though her marriage is a mess and she has told Mark plenty of lies, she makes up her mind that she should at least talk everything over honestly with him, and see where things go from there.

When I read that book in 1980 or thereabouts, I didn’t understand it in the way that its (male) author probably intended—that is, a psychological drama about a mentally unhealthy woman slowly learning to accept normal social behavior. Instead, Marnie came across to me as a feminist archetype, insistent on staying in control of her own identity. Yes, she definitely had some issues to work on; but she wanted to deal with them herself, rather than meekly conforming to other people’s demands.

To that extent, Marnie was a positive influence on my younger self’s development because she gave me confidence that I had the power to control the narrative and to define myself. Marnie’s worldview left much to be desired in other respects, though. She was very defensive and resentful, both toward others and herself; she never felt safe, but was always afraid she’d make a mistake and everything would come crashing down. She sneaked around like what she was—a thief.

The overall message I got from this story had much in common with what I’d taken away from The Left Hand of Darkness—that I could change the course of events, but that doing so would always meet with resistance of one sort or another.

When I was younger, I liked the drama of taking control of the narrative, but I didn’t understand how much harm could be done by the cumulative stress from subconsciously expecting resistance and enemies. I also didn’t understand that it tends to be a self-fulfilling prophecy—when we’re constantly on our guard looking for enemies, we generally manage to find them. When we feel that we can’t ask for help without something bad happening as a result, that is likely to come true as well.

So I took an imaginary trip to England a half-century ago, wanting to check up on Marnie and see how things had been going in her life since she made the decision to stay in her marriage. I found her standing on a path in a well-tended garden with masses of lovely roses on either side, on a bright cloudless July morning. She was heavily pregnant, and her eyes were half-closed as she stood quietly, breathing in the fragrance. Bees buzzed contentedly in the blossoms.

(Creative Commons image via flickr)

“You’re looking very well,” I told her, with what I intended as a reassuring smile.

Marnie’s lips twitched nervously in response. “It’s rather a lot to get used to—marriage and motherhood, I never felt that I’d be suited to either; but here I am. And you’re not real, are you? I never let anyone know this, but I was always afraid of going mad.” She touched my left arm cautiously, and her fingers passed right through it.

“No need to worry,” I said, as a bee hovered above my other arm. “It’s only imagination, both yours and mine. Imagination is natural and healthy. Most people would do better if they had more of it. Sometimes it can get to be a problem, though, when we imagine that accepting help and support can only tie us down and rob us of personal power. I’ve been wondering—how have you managed those feelings? You look as if you’re happier than you once were.”

“Well, it has been a struggle some days,” Marnie confessed, her voice low, as if she worried about being overheard even though we were alone in the garden. “I’ve been seeing another psychiatrist, a nice older lady. A good mother figure, you might say; and it helps that I chose her myself, instead of Mark demanding that I visit someone he had already decided on. He didn’t mean it that way, I understand now; he was only trying to be helpful, and he never balked at leaving the choice to me after I explained how I felt.”

“Yes, that’s it right there.” I nodded, appreciating how simply this young ex-thief had summed up a complicated issue that I’d struggled with myself. “When people insist we do things a certain way, and it’s not what we would have chosen for ourselves, usually that doesn’t mean they are controlling or unreasonable. It just means they haven’t managed to step outside their own perspective for long enough to see that there might be other ways we’d prefer. And we don’t need to be defensive and argue about it—rather, we can thank them for their help and perhaps try it their way for a short time, without feeling as if they’ve forced us to do something we don’t want forever. As time passes, there will always be more opportunities to set healthy boundaries and to shape our lives into patterns that better suit us.”

Marnie smiled again, this time in genuine happiness, with a flash of straight white teeth and the corners of her mouth crinkling cheerfully. “I’d invite you in for tea, but as you’re not real I suppose you don’t need any. Besides, I expect Mrs. Leonard, the housekeeper, might get a bit of a fright if she saw me having an imaginary tea party like a little girl.”

“Oh, you never know about that, Marnie. She might wish she could have a pretend tea party herself!”