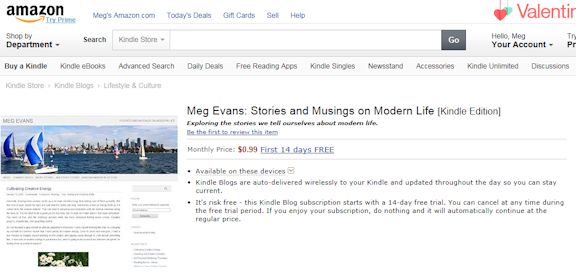

An investment advisor that offers its services through my employer’s tax-deferred savings plan tried to drum up more business recently by sending employees a retirement evaluation. Mine had a cutesy red-light graphic and criticized my investment choices as too aggressive for someone my age. Having more stocks rather than bonds apparently means that I can’t be confident of turning into a pumpkin at the stroke of midnight upon reaching the magic age, or something of that sort.

At the risk of branding myself a modern-day heretic, I’ve never had any desire to create either a bucket list or a retirement activities list because no matter what I might put on such a list, I can’t see myself staying interested in it forever. I contribute regularly to the investment plan because it’s always good to have savings, no matter what I might decide to do with them, and because the company match is free money. But I never could make sense of the cultural expectations that every responsible adult should work like a beast of burden for several decades, with the goal of never working again, and that everybody’s life should be fully planned out.

Of course, some folks are indeed happily retired and enjoying the activities on their list. If that’s you, well then—more power to you! But all too often, people retire just because they were told it’s what everyone should want, and then they have no idea what to do with themselves. Maybe they thought they’d enjoy something, but then it ends up not being as much fun as they imagined. It’s a sad fact that depression and suicide rates spike among the newly retired. Shifting gears all of a sudden and leaving behind a busy career can result in feeling lost and adrift, with no meaningful purpose or identity.

Instead of making conventional plans for retirement, Millennials tend to prefer the “financial freedom” approach of keeping their expenses low while they’re young, so that they can build up hefty savings and change jobs or start businesses whenever they feel like it. Buying a house is not the major accomplishment that it was for past generations, but is an expensive burden to be avoided. This works great for people who enjoy frequent travel and the challenge of becoming acclimated to new environments, as well as for minimalists who are not emotionally attached to their stuff.

I would describe myself as somewhere in the middle. I like the comfort and stability of owning a house and keeping a job for a longer period, but I also value new experiences and flexibility. I wouldn’t want a lifestyle of constant travel, but it might be fun to live and work in another country for a year or two. At some point I’ll want to build a new house (I sketched out a floor plan for fun last month). With so many career possibilities in the modern world, it seems likely I’ll develop other work-related interests.

So, what’s my best approach to finances? Never doing any work again is not my goal, and I can reasonably expect to be around for another half-century because of a family history of longevity, so all those computer models based on actuarial tables are not much use to me. Freedom to pursue any interests I may develop is a much more appealing prospect, but how can I put a number value on choices I haven’t yet made?

I suppose finances are like anything else—moderation and incremental changes generally tend to work best, while making course corrections as the need arises.