All parts of this story are consolidated on one page here.

Ina carefully laced her bandaged feet into John’s oldest pair of boots. Scratched and torn, those boots didn’t look as if they would survive much more than one wearing; but they fit well over her thick cloth bandages, and Ina expected they would last long enough for a ghost-hunting expedition to the nearby river.

Whether she should have agreed to go—well, that was another question entirely. To free the wailing spirit of Nellie’s sister from a curse that might not exist seemed a fool’s errand. Even so, if she could make Nellie happier simply by trying, the short walk would be worthwhile for that reason alone.

Both children still slept soundly, and John was close by to watch over them. Nellie already had taken an impatient step toward the porch stairs. Ina got up slowly, relieved to find that her feet were not in much pain when she put weight on them. She followed Nellie down from the porch and into the woods. After the first bend in the path, she noticed raspberries ripening in the tangled undergrowth.

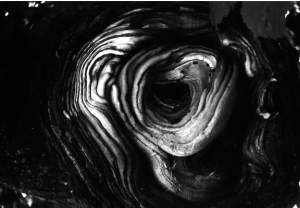

(Creative Commons image via flickr)

Ina had picked raspberries somewhere nearby, almost a year ago, when she’d stayed with Nellie for a day after waking to find herself beside the lake. She had fallen asleep after walking through the woods, and before that she’d come from…

Just as the image of a well-kept house and a rose garden began to come clear, Nellie started talking, and the memory faded as quickly as it always did.

“That’s where I found Hetty’s body, on the other side of that stand of sycamores. The river was still far out of its banks after the storm.”

Looking ahead, Ina couldn’t see the river, but she could hear water softly trickling not far away. Today’s rain had not lasted long enough to increase the flow by much. Behind the sycamores that Nellie had pointed out, there was a faint, reddish gleam through the leaves, like a pale reflection of the sunset.

Ina shook her head at that thought; it was high summer, with many hours of sunlight remaining. Still, there had been something—what could it have been? Not fire, certainly; she’d have sensed that, even with her magic depleted by healing Mabel. Quietly sending a tendril of awareness in that direction, Ina couldn’t sense any life beyond the usual forest creatures, but she was left with a general sense of unrest.

“I hear Hetty. She just started crying now,” Nellie announced, turning off the main path to follow a narrower track around the trees, in the direction of the river. The mysterious reddish light grew brighter, and Ina began to see gleams of white through it.

All at once, the outline of a young woman in a long white dress took form. The woman knelt in the grass near the sycamores, her head bowed, with a shimmering net of fiery red energy surrounding her.

Ina still couldn’t hear anything beyond the peaceful sounds of birdsong and the river’s gentle flow, but the fiery net assaulted her other senses with a ferocious blast of emotions—anger, hate, a burning need for revenge, an unyielding refusal to forgive. Unrest, indeed; that word came into Ina’s thoughts again. Unrest, or no rest; she was still trying to sort out the word’s significance when Nellie spoke again.

“Can you hear my sister?” Nellie stood within arm’s reach of the imprisoned spirit, evidently unable to see or feel any of what Ina was sensing.

Ina looked up from the kneeling figure and met Nellie’s eyes as she began to understand what had happened on that long-ago midsummer day.

“No, but I can see the curse.”